Xeroderma Pigmentosum-Neurological Disease (XP-Neuro)

XP-neurological disorder (XP-neuro) is a member of a group of diseases called DNA repair disorders. These disorders cause problems with fixing damaged DNA. Damage to DNA happens constantly. It is caused by such things as ultraviolet light in sunlight and flourescent lights. Other things that can damage DNA include ionizing radiation from X-rays and other medical devices. Chemicals, normal processes in cells, and other substances or processes can also damage DNA. Because damage occurs all the time, living things have evolved many systems for fixing it. There are proteins that recognize that damage has occured, enzymes that remove the damaged DNA, and enzymes that insert new, undamaged DNA bases. This list is not exhaustive. When a person has a defect in one of these repair systems, disease results. If the problem is in a system that fixes damage from UV light, a person may be extremely photosensitive, with some people burning badly after only a brief exposure on a cloudy day. Overall, DNA most people with DNA repair disorders have a high risk of cancer.

In XP-neuro (and all diseases in the XP group), repair of UV-induced damage is defective. Patients tend to be very prone to sunburn as a result, although not all patients have this problem. Some XP and TTD patients do not sunburn easily, in spite of their inability to repair damage done by UV light (1). XP-Neuro patients tend to be in the group that burns easily. This fact actually tends to have a protective effect, because these patients often naturally avoid UV light as a way of minimizing painful sunburns. In many patients, a sunburn following minimal sun exposure is the first sign of disease. Unfortunately, the sunburn may be mistaken for child abuse.

Clinical information

XP-Neuro is the neurological form of xeroderma pigmentosum (for more infomation, see our XP page. As noted above, XP affects a person's ability to fix damage caused by UV light. The greatest source of UV light on earth is the sun. Other everyday sources include flourescent lights, halogen lights, high-intensity discharge lights (fe.g., in car headlights), tanning booths, mercury vapor lamps (often used in streetlights), and standard incandescent light bulbs. In addition, germicidal lamps, black lights, and some kinds of lasers produce UV light.

XP patients must be protected from UV light. If they are not protected, they will develop skin damage resembling what is shown in the pictures on this page. The level of damage and disfigurement depends on the person and on the level of exposure. If a patient is not protected properly, severe disfigurement, tumors and cancers, blindness, and even death can result. The damage often begins to show at very young ages. In addition, an infant may burn severely after spending ten minutes outside in or near sunlight. XP burns can be so severe and develop so quickly, they can be mistaken for child abuse. While sunscreens help, the best protection is avoidance of light. In cases where a patient must go outside during the day, heeavy garments, eye protection, and hats are essential.

In general, patients with the neurological forms of XP tend to burn easily (1). While this is a more painful response than the response of XP patients who do not burn, the burns tend to encourage patients to naturaly avoid the sunlight and other sources of UV light, which reduces their skin cancer risk. Problems in XP and XP-Neuro include the following:

- Pigmentation abnormalities of the skin (see the photo of the girl above right)

- Solar lentigines (dark freckle-like discolorations that don't fade in winter)

- Actinic keratoses (precancerous skin patches; thick, crusty, or scaly)

- Skin cancers (basal cell, squamous cell carcinomas, melanomas)

- Conjunctivitis (redness/inflammation the whites of the eye)

- Atrophied skin

- Very dry skin

External manifestations

- Intellectual disability that may be progressive (get worse with time)

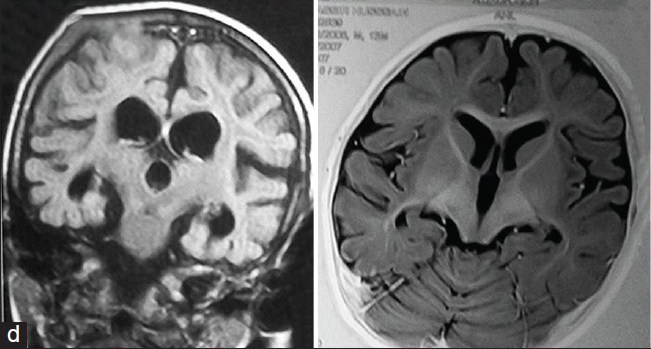

- Brain atrophy and other brain abnormalities detectable on scans

- Abnormal deep tendon reflexes (absent or reduced)

- Delays in speech development

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Hearing loss

- Seizures

Neurological manifestations

In general, the neurological problems in XP-Neuro can get worse with time. For example, patients may lose motor skills and cognitive skills. They may also develop hearing and speech problems that may get worse. A minority of patients deveop dementia and choreoathetosis. The term choreoathetosis refers to involuntary movements that are a combination of irregular, abrupt movements (chorea) and twisting/writhing movements (athetosis). There is a video link on the right showing a non-XP patient with choreoathetosis.

XP-Neuro is confirmed by testing for mutations in the genes XPA XPB, XPD, XPF, and XPG. The genes most commonly involved in non-neurological cases of XP are XPC and XPV. Patients with these mutations tend to not burn easily. Strict avoidance of the sun in this group may be more of a challenge. The US National Institutes of Health maintains a list of laboratories that do testing (see link at right). If you suspect that your child or a family member has XP-Neuro, your doctor can obtain a sample send it to a testing center.

If you suspect that you or your child has XP, check with your family physician, who will compare your child's signs and symptoms with those known to occur in XP. If your child's doctor isn't familiar with XP, the information in reference 2 may help. There are a number of other freely available sources of information on XP, including those cited in the columns at the right. There are also different freely available publications with photographs of XP patients of different races and ethnicities (3,4), and an account of living with the disease written by a parent (5).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for XP-neuro includes the other XP-related diseases, including XP-CS, and trichothiodystrophy/TTD. The skin problems are effectively the same in all three conditions and require the same management: strict avoidance of sunlight and other sources of UV light. Although the level of sensitivity to UV light differs in the three conditions, XP patients are at increased risk of UV-associated malignancies and UV-associated disfigurement. TTD patients do not appear to have an increased cancer risk (6,7). If the results of genetic testing are available, clinicians may wish to monitor patients with mutations in genes associated with neurological forms of XP and/or schedule one or more visits with neurologists.

XP-neuro may be distinguished from TTD by hair and nail abnormalities that are common in TTD, but that do not generally occur in XP-neuro. It may be distinguished from XP-CS by the facial phenotype that is unique to CS, although in cases that progress relatively slowly, this phenotype may not be evident until a patient is older.

Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (RTS) is also similar to XP, in that patients are born with normal skin that shows pathological changes in infancy. RTS patients usually develop a rash-like skin condition called poikiloderma on their cheeks. Poikilodermic rashes are hypo- and hyperpigmented, meaning that they have areas of too little and too much pigment. Clusters of thin blood vessels called telangiectases are often seen under the skin, as is the case with XP patients. Like XP patient, their skin tends to atrophy. skin atrophy. Pokiloderma usually appears before a patient's second birthday, with most children developing it well before then. It typically spreads to other body parts, including the extremities and the trunk, and it may resemble a sunburn. Clusters of blood vessels called telangiectases are often seen under the skin, as is the case with XP patients. Like XP patients, RTS patients are also at increased risk for skin cancer.

RTS patients also have sparse hair (like trichothiodystrophy patients), juvenile cataracts (like some XP, CS, and XP-CS patients). Also like XP patients with neurological manifestations, they may be short in height. While intelligence is usually normal, patients may have intellectual disabilities.

In addition, some RTS patients are sensitive to sunlight, and their rash may be worse on sun-exposed skin. Unlike XP patients, however, the rash on RTS patients can occur on non-sun exposed areas, such as the buttocks. This difference may help distinguish the two conditions in the absence of genetic testing. RTS is caused by mutations in the gene RECQL4. Another abnormality that can help distinguish RTS from XP-neuro is that many RTS patients have absent bones (including forearms or thumbs), malformed bones, and/or fused bones; see our RTS page for photographs. These problems are not generally associated with any of the XP disorders.

Since 1999, the National Institutes of Health has been running a large study of people with TTD, Cockayne syndrome, and xeroderma pigmentosum. The study is called Examination of Clinical and Laboratory Abnormalities in Patients with Defective DNA Repair: Xeroderma Pigmentosum, Cockayne Syndrome, or Trichothiodystrophy. The goal of the study is to document health problems occuring in people with these diseases in order to understand them as completely as possible. More information about the study, including contact information, is available at clinicaltrials.gov.

References

- 1. Sethi S (2013) Patients with xeroderma pigmentosum complementation groups C, E and V do not have abnormal sunburn reactions. Br J Dermatol. 169(6):1279-1287. Abstract on PubMed.

- 2. Lehmann AR et al. (2011) Xeroderma pigmentosum. Orphanet J Rare Dis 6:70. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-70. Full text on PubMed.

- 3. DiGiovanna JJ et al. (2012) Shining a light on xeroderma pigmentosum. J Invest Dermatol 132(3):785-796. Full text on PubMed.

- 4. Mareddy S et al. (2013) Xeroderma pigmentosum: man deprived of his right to light. Sci World J 2013:534752. doi: 10.1155/2013/534752. Full text on PubMed.

- 5. Webb S (2008) A patient's journey. Xeroderma pigmentosum. BMJ 336(7641):444-446. Full text on PubMed.

- 6. Faghri S et al. (2008) Trichothiodystrophy: a systematic review of 112 published cases characterises a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. J Med Genet 45(10):609-621. Full text on PubMed.

- 7. Lambert WC et al. (2010) Trichothiodystrophy: Photosensitive, TTD-P, TTD, Tay syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol 685(6):106-110. Abstract on PubMed.

- 8. Tamhankar PM (2015) Clinical profile and mutation analysis of xeroderma pigmentosum in Indian patients. Ind J Derm Ven Lepr 81(1):16-22. Full text from publisher.

- 9. Zheng JF et al (2015) Clinicopathological characteristics of xeroderma pigmentosum associated with keratoacanthoma: a case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Med 7(10):3410-3414. Full text on PubMed.

- 10. Halpern J et al (2008) Photosensitivity, corneal scarring and developmental delay: xeroderma pigmentosum in a tropical country. Cases J 1:254. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-254. Full text on PubMed.